Ted Smith plays with the phrase “The End of Theological Education.” Is it the END?

Or, what is the purpose of theological education.

The answer is, “YES,” depending on your perspective.

Allow me to visually walk you through this book.

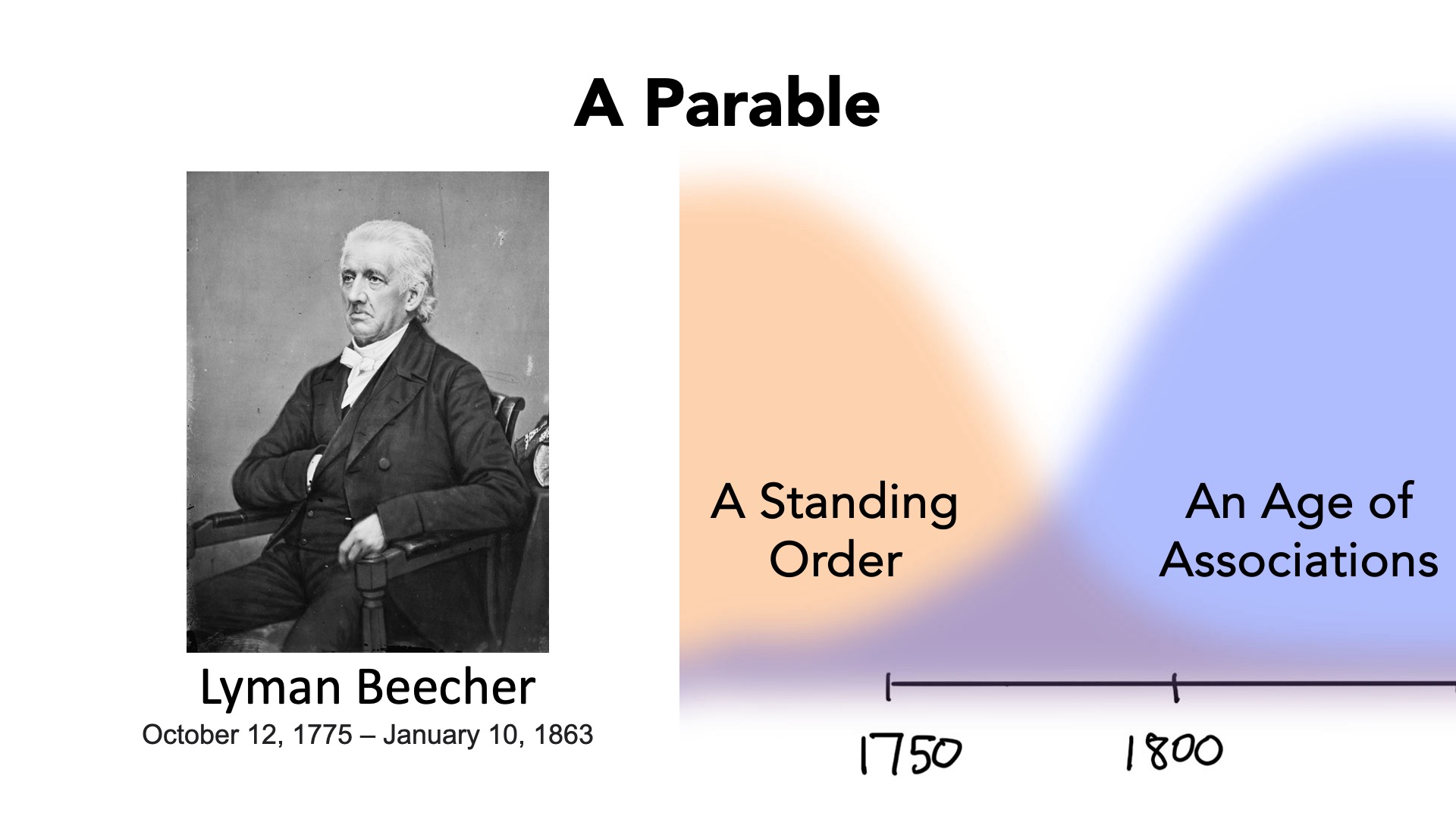

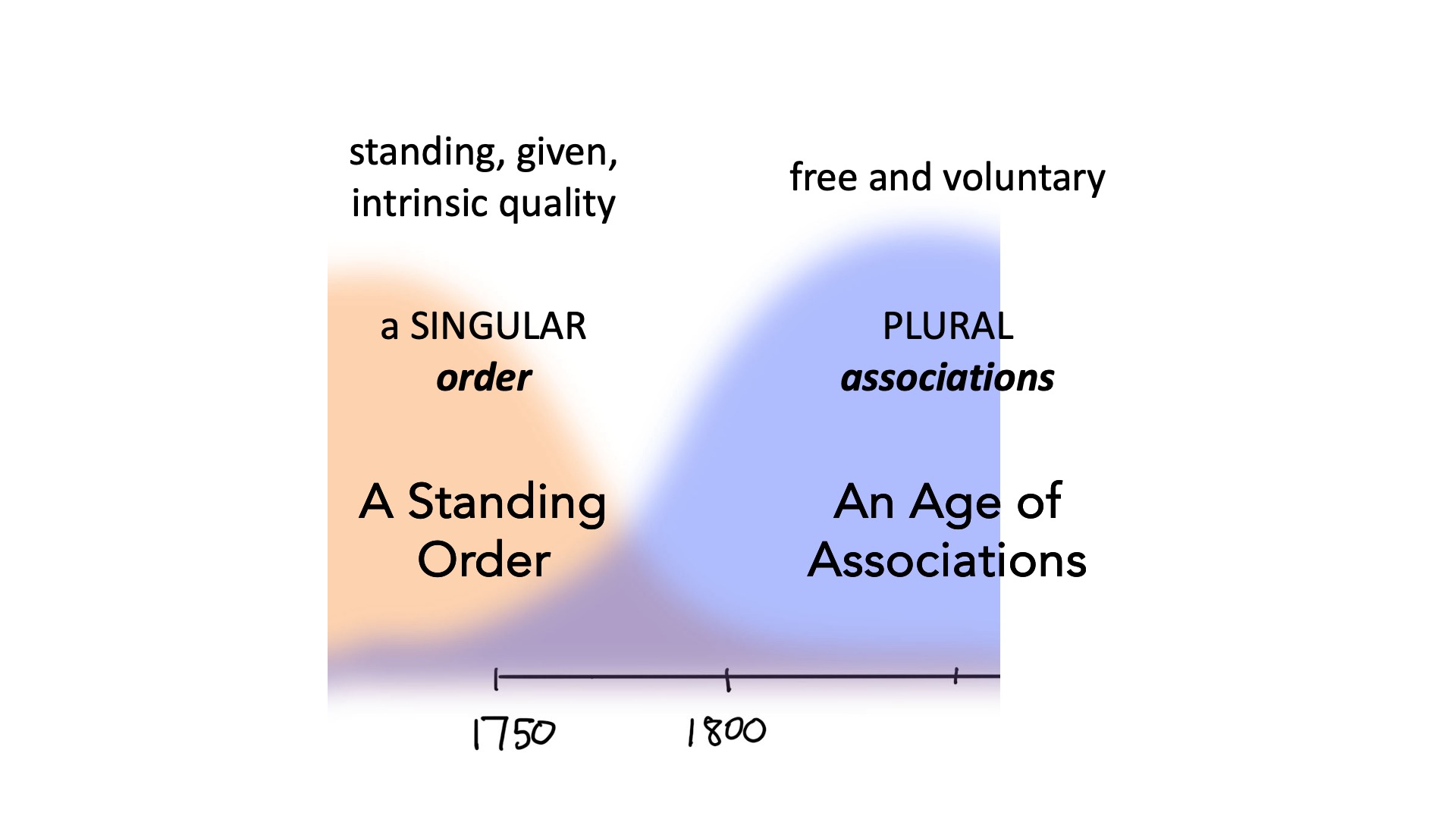

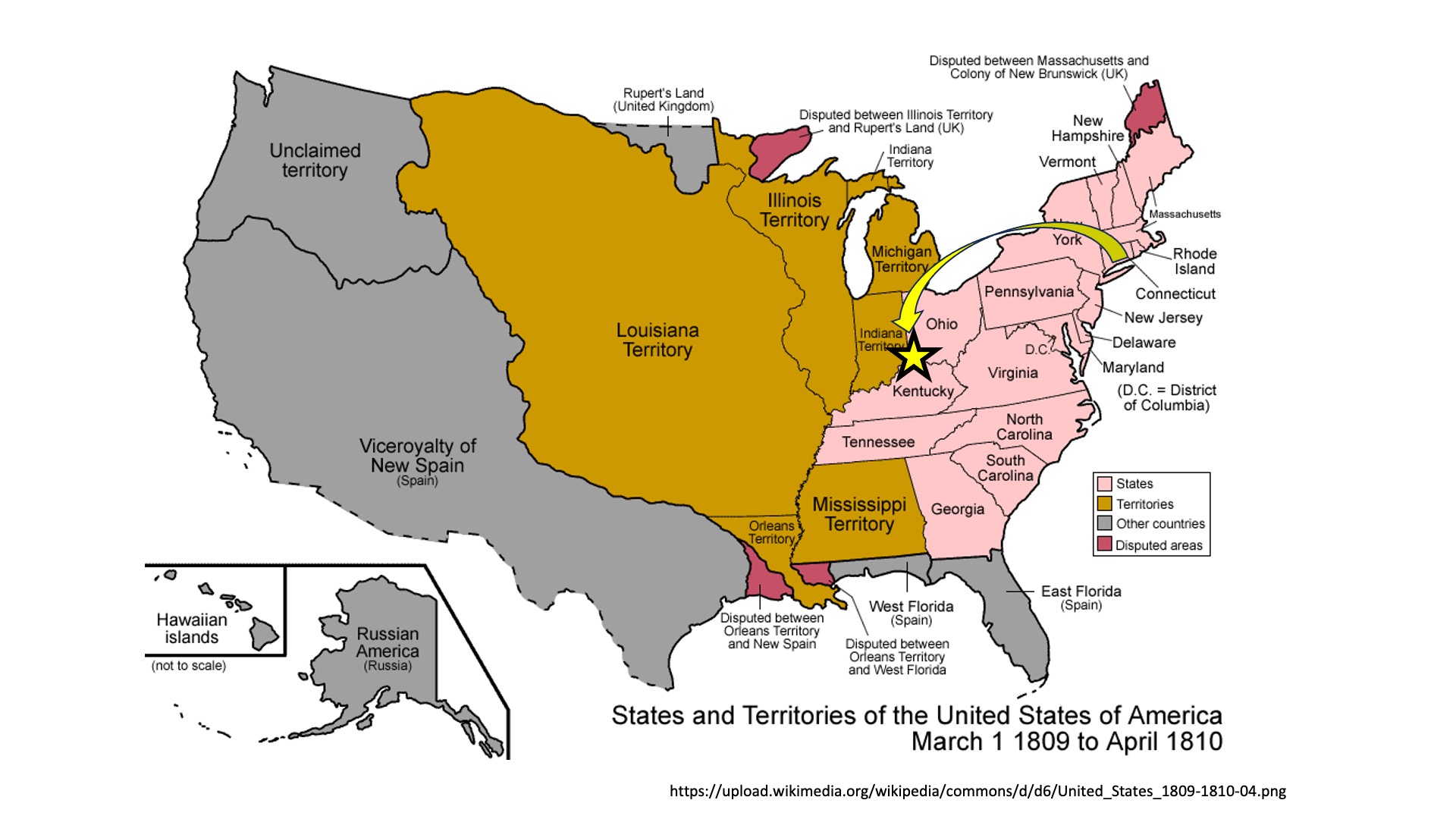

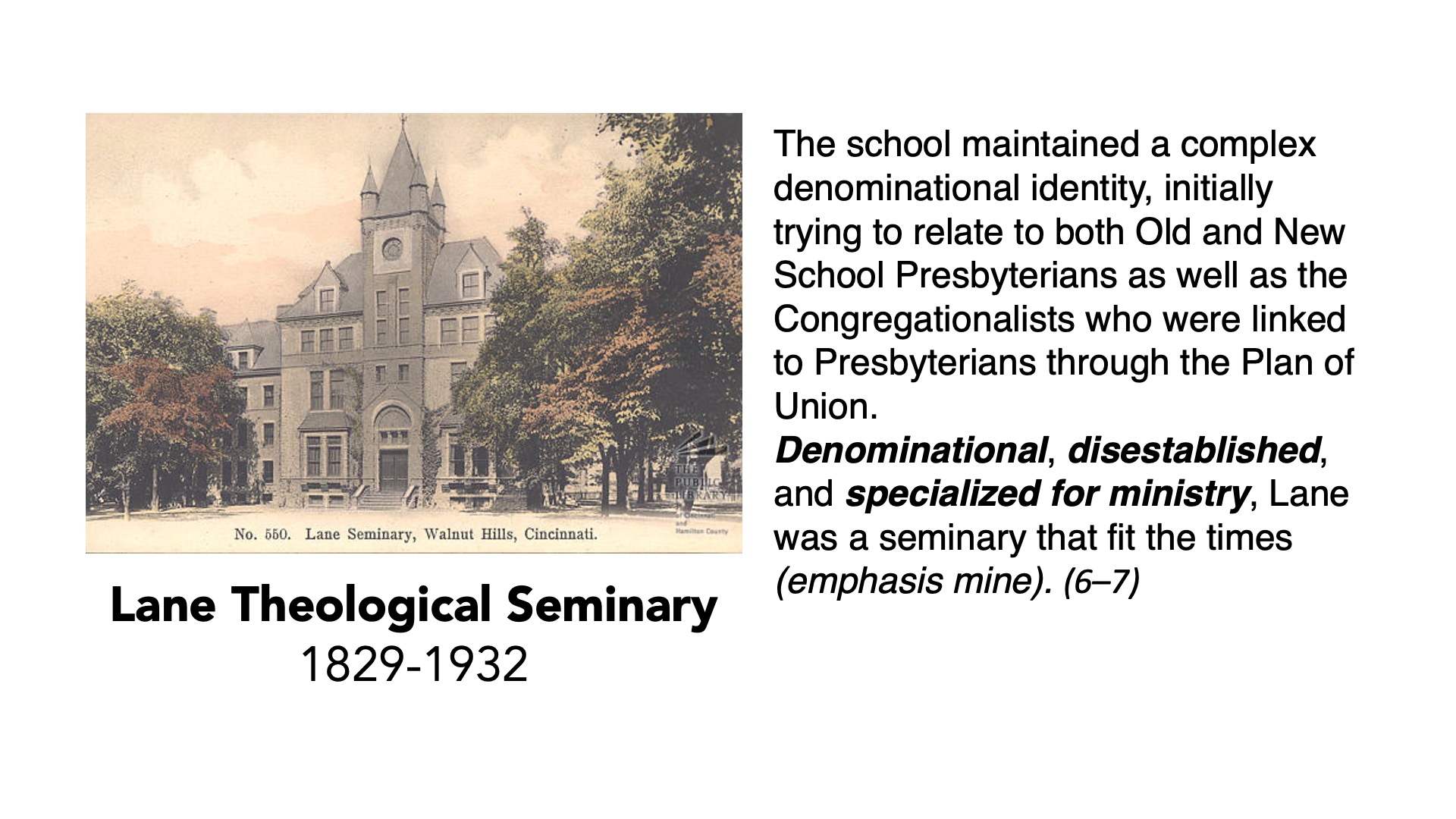

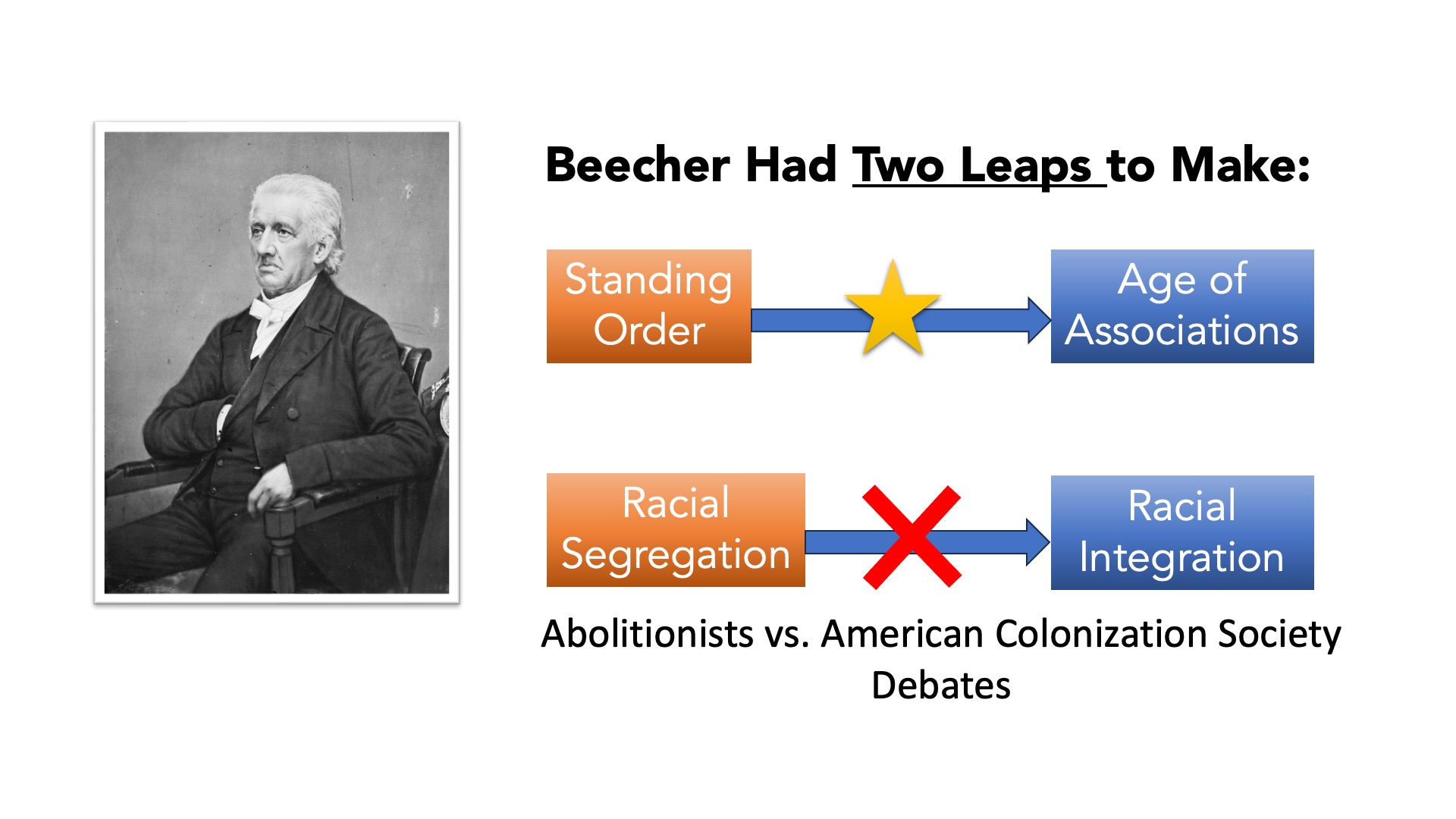

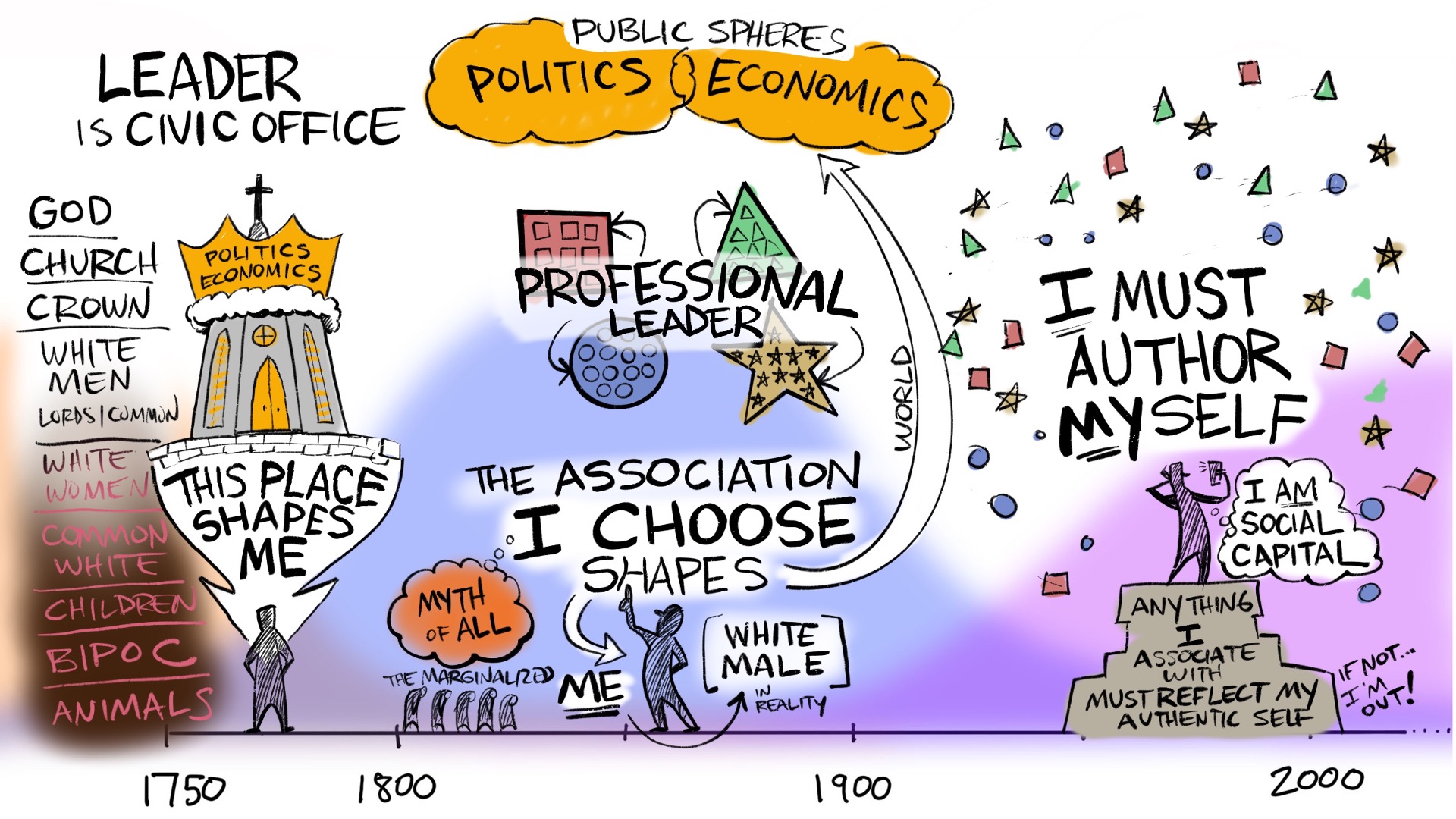

Smith makes his argument in four movements. First, he tells the story of Lyman Beecher at the turn of the nineteenth century to offer a case study of how leadership can adapt to massive cultural shifts in the social imaginary of a nation.

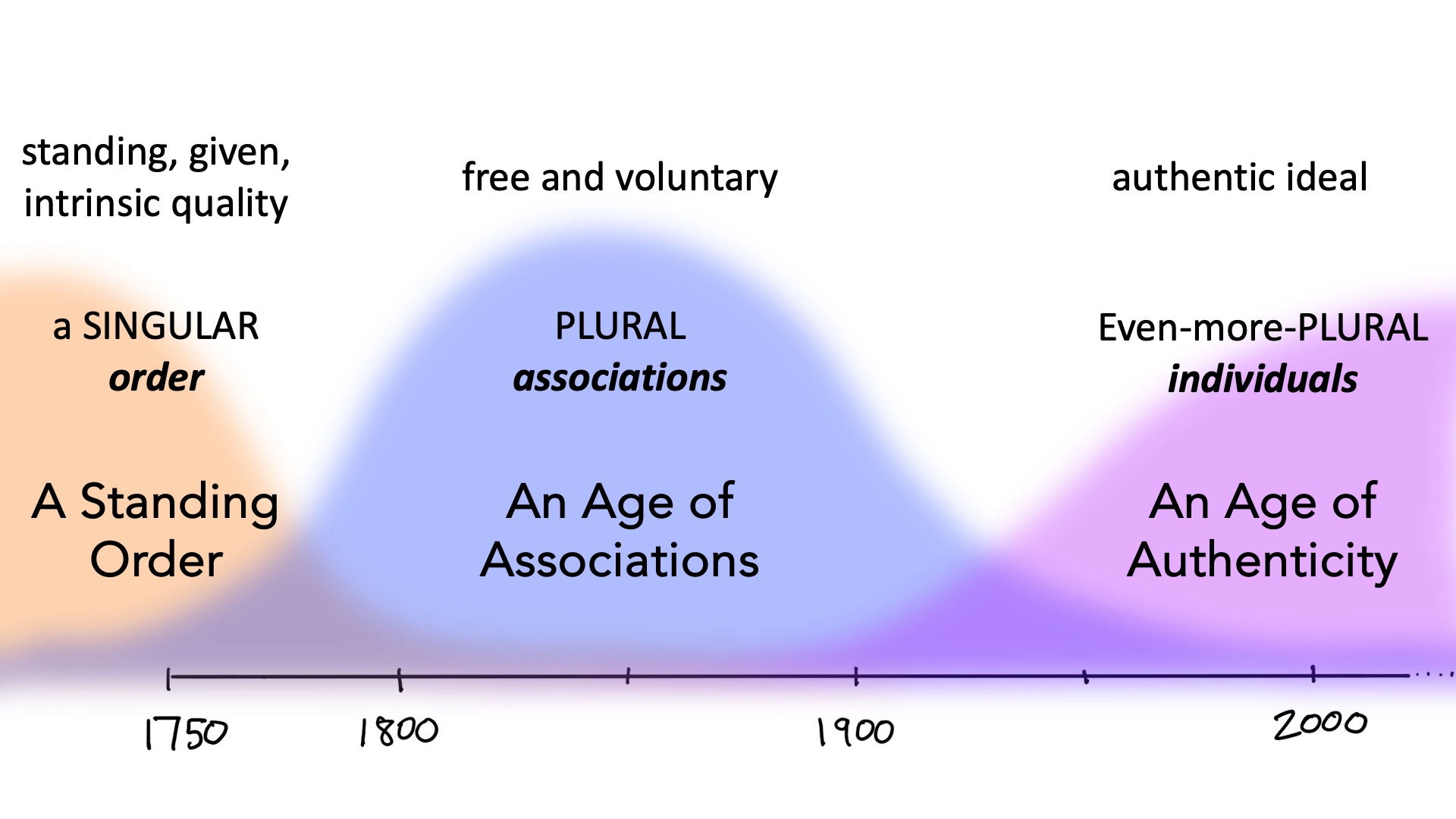

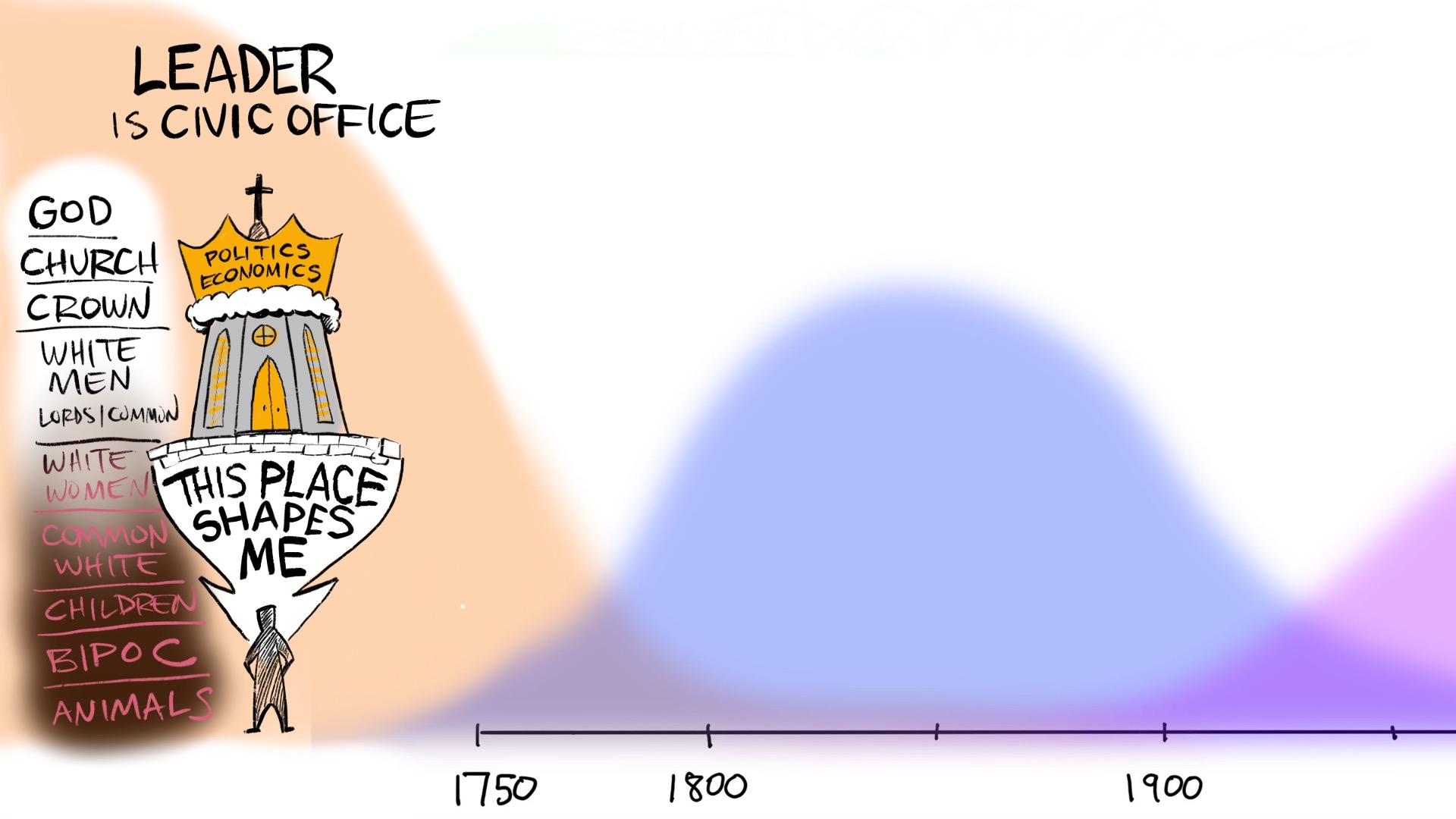

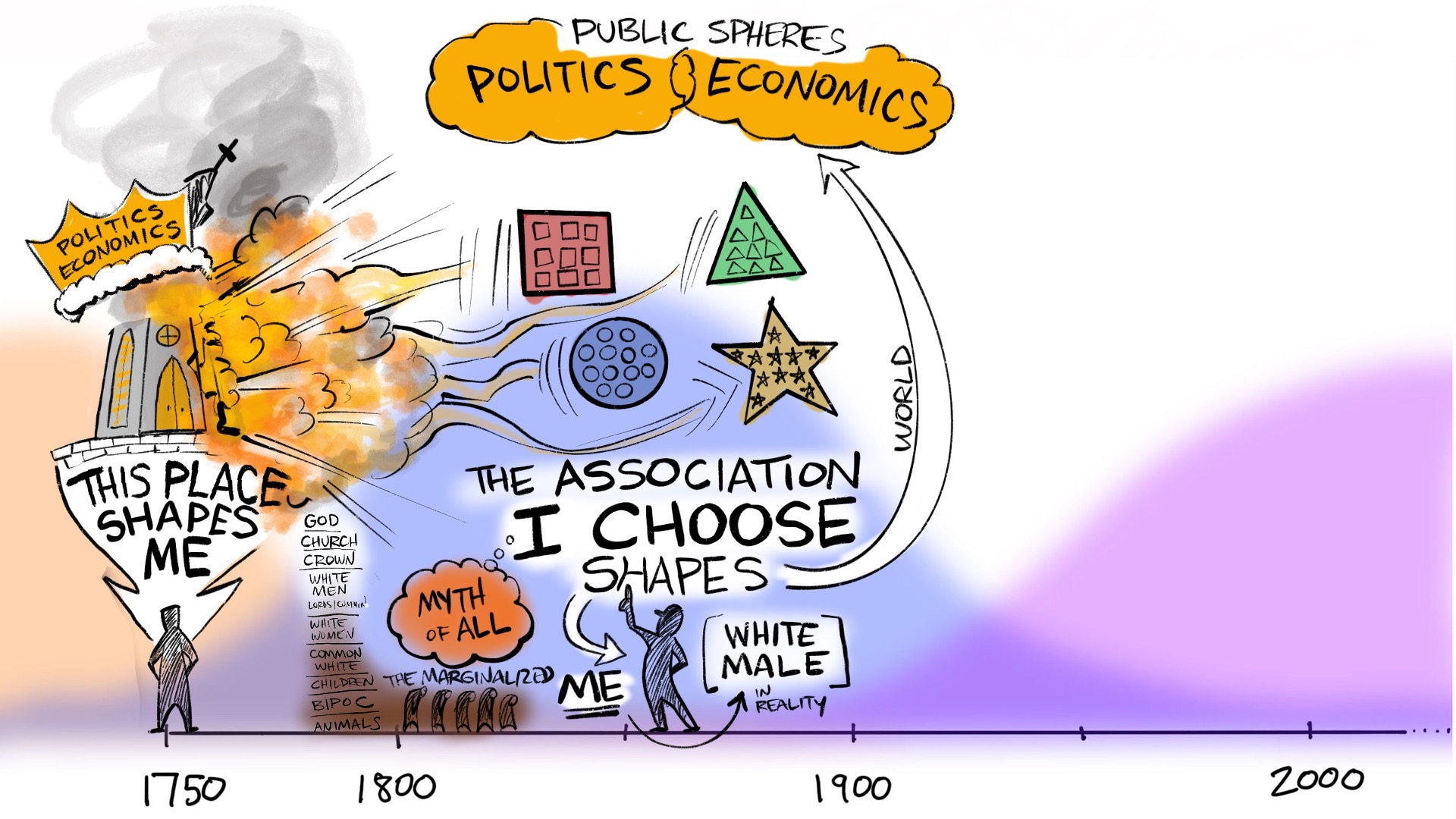

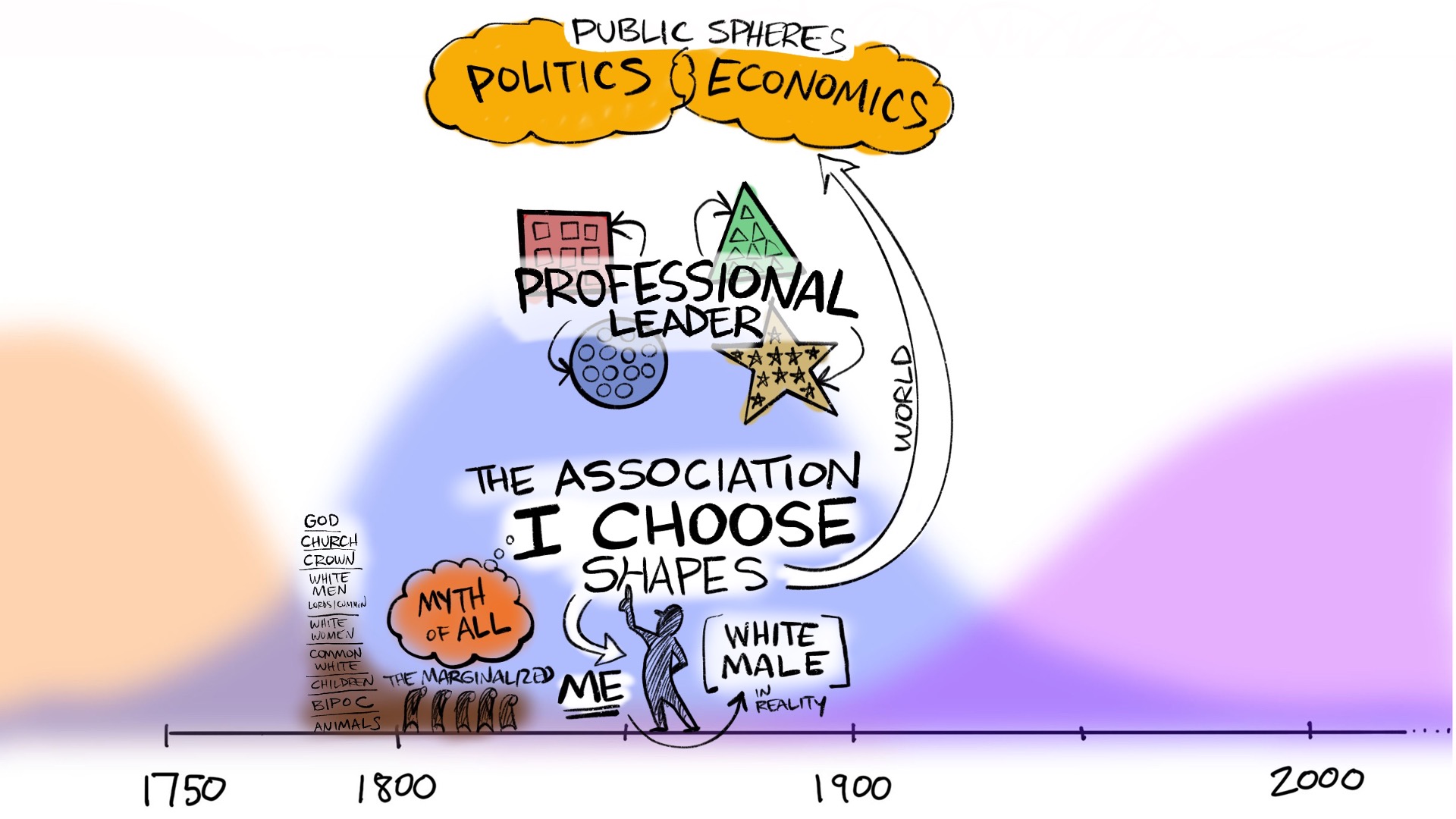

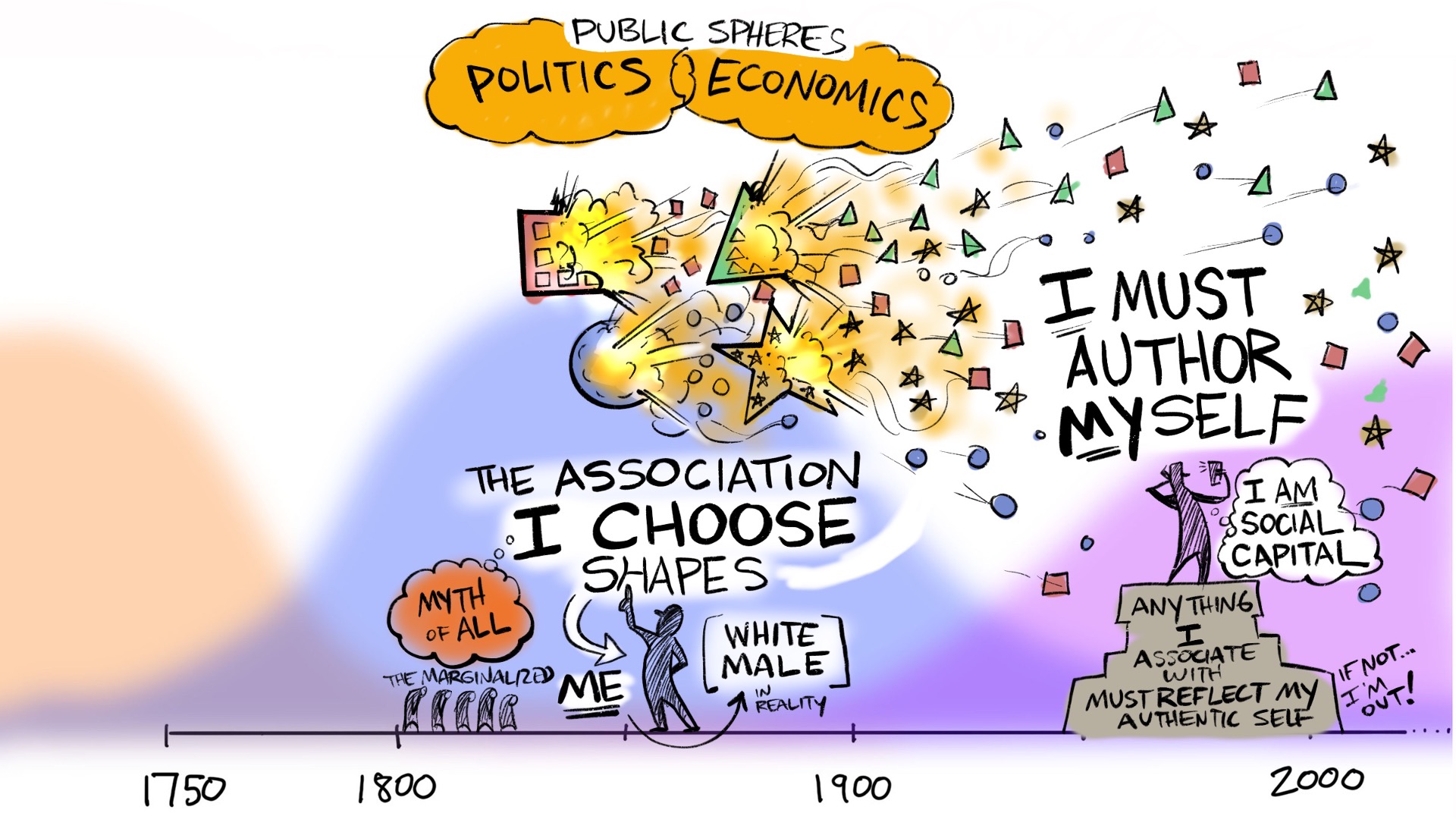

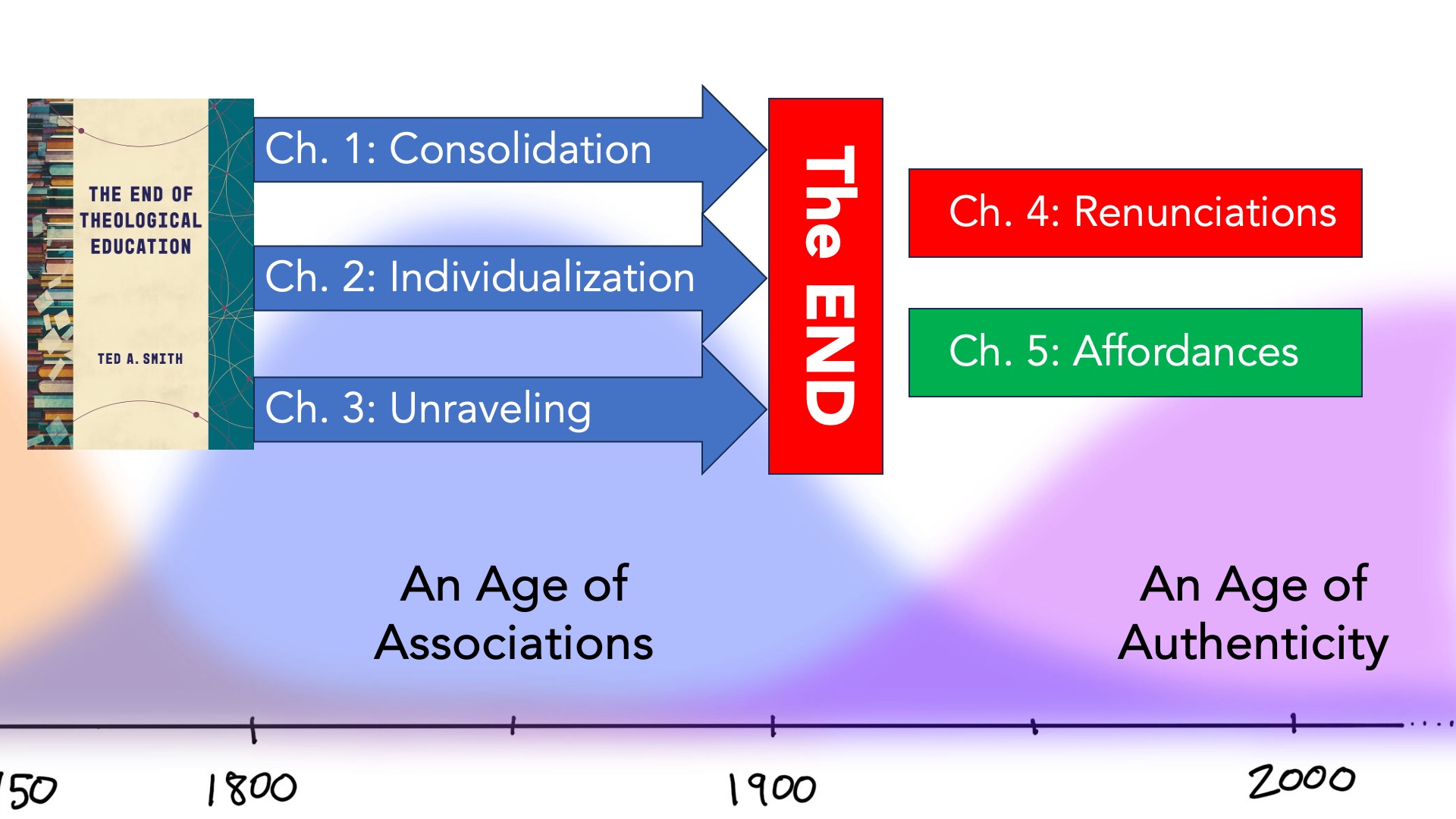

The second movement of the book covers three chapters in which Smith analyzes our current shift from, according to Charles Taylor, the Age of Association to the Age of Authenticity. He notes the impact it has on our current social imaginary, the church, and institutions of theological education in the early twenty-first century. In this section he identifies the consolidation of theological education to that of a professional degree that services voluntary associations. Then he names the power of individualization, as opposed to individualism, that is fracturing the voluntary association and placing the impetus of personal identity on the will and merit of the individual self, whether the individual wants it or not. Finally, he names how the twin engines of identity and expression are unraveling denominations, congregations, the profession, and theological education itself.

The third movement is a brief interlude in which Smith explores the meaning of the word end. He reclaims Jeremiah’s vision and notes that the prophet was not proclaiming the end of the world. Rather, he was announcing, and reminding the people, of the purpose of the covenant that is written on their hearts. Smith claims this as the hope of and the chief telos—purpose—for theological education: to know God.

Finally, Smith’s shift toward purpose and hope in the previous section leads him to the fourth movement of the book in chapters four and five. Here he names the negative aspects of the Age of Association that we must renounce. Leaders who have been trained in modern professionalism must not try to manage their way out of this problem and back to the old status quo. Instead, we must renounce the professional model and find a new vision for leadership.

In chapter five he names the positive aspects of the Age of Authenticity that offer affordances for us to explore fresh opportunities to carry out the Gospel of Jesus and reclaim the true end of theological education. God is doing, and has always been doing, something in the world as new ministries continually form in unexpected places, outside of judicatories and credentialing systems. Smith encourages us to imagine a world in which institutions of theological education do not see themselves as gate-keepers and credentialing agencies. What if theological education cultivated places that recognized the leaders that God is raising up and partnered with them in “leader-full” experimental moments to further equip them and deepen their knowing and being known by God.

A Brief Evaluation

This book is an important contribution to the body of literature designed to help today’s Christian Public Leaders—both in the local context and in the institutions of higher education—to both understand and to navigate the swiftly changing spiritual landscape. I offer one positive evaluation and one room-for-growth observation.

First, one of the strengths of this book is Smith’s intentional awareness of his own place of privilege in the story of Theological Education. He names the reality that Protestant theological education, particularly in the United States during the Age of Association has serviced white, male privilege, reflecting the ethos of professionalism across the spectrum of disciplines. The story of the end of theological education in the age of association and the affordances that the age of authenticity gives it is not a universal one. Many Christian traditions, particularly those of people marginalized by white, male supremacy, have resisted the professionalization of the clergy and the credentials of the academy all along. People who are currently in a context like this might read this book and think, “They are finally catching on. It’s about time.” Regardless, it is important for all leaders to be able to articulate the powerful societal forces that are driving our decision making in our local contexts.

Second, the one critique of this book is that it begs the question, “Yes, but how?” It is one thing to succinctly diagnose the situation. It is another thing to prescribe practical suggestions for how the institutions of theological higher education can effectively renounce all the demons from the past that keep them bound and experiment with the affordances that the Age of Authenticity offers. This is a mild critique, since one volume cannot hope to accomplish both diagnosis and prescription adequately. Perhaps volume two, “What Now?” is in the works.

Could you reduce your emails to me to only one a week?

Richard, you should be able to click on your emails to manage subscription. I do have a weekly summary option. I’ll see if I can do it on my end as well. Sorry for clogging up your inbox. 🙂

done! You should only get emails on Mondays. Thanks for reading.

This is a really painful reality right now. Thanks for the summary.

agreed. We have many adaptive challenges ahead. AND, that is where the Holy Spirit thrives!