There’s a question I hear again and again when I talk with faithful church members—especially among older generations:

“Why don’t my children or grandchildren go to church anymore?”

It’s not just a question about attendance. It’s a question about belonging, faith, and identity. It carries a deep ache, a kind of spiritual disorientation. For many of us, church has been the center of our lives for as long as we can remember. It’s where we found meaning, community, and direction. To see the next generations drift away can feel like watching something sacred unravel.

In this reflection—and in the video that accompanies it—I try to offer a way of understanding this moment. I don’t pretend to have all the answers, but I believe this story is larger than any one congregation, denomination, or family. It’s the story of how our culture has shifted—how the church moved from the center of society to its margins—and what that means for discipleship today.

Watch the video or scroll down for a short essay version of it.

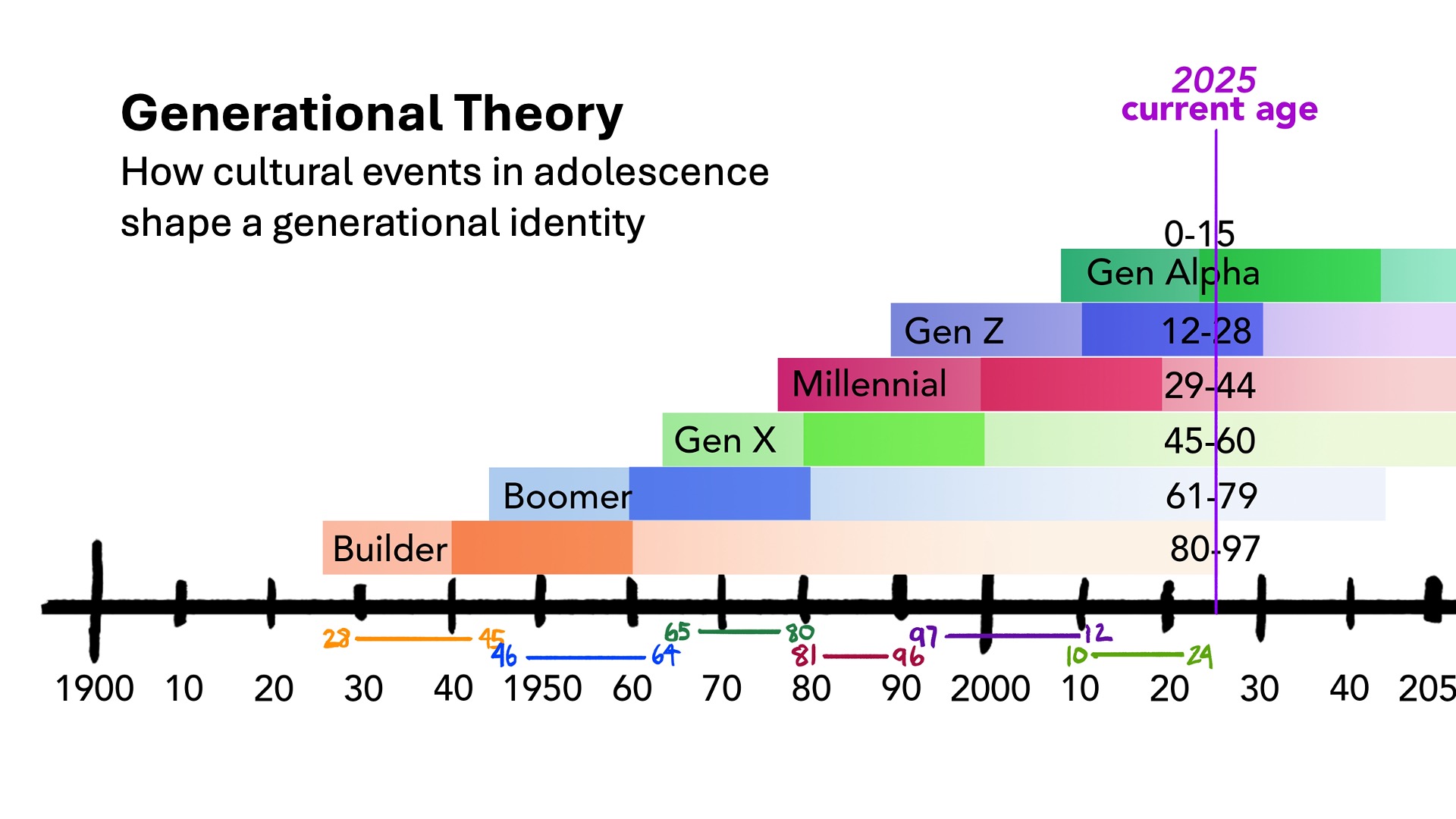

Below is a sketch of the generations. The darker bands indicate when each generation went through adolescence. Place yourself on this map and then pay attention to what was happening in society when you were coming of age.

Three Voices That Shape This Conversation

My thoughts in this talk are shaped by three scholars whose work has helped me see the bigger picture.

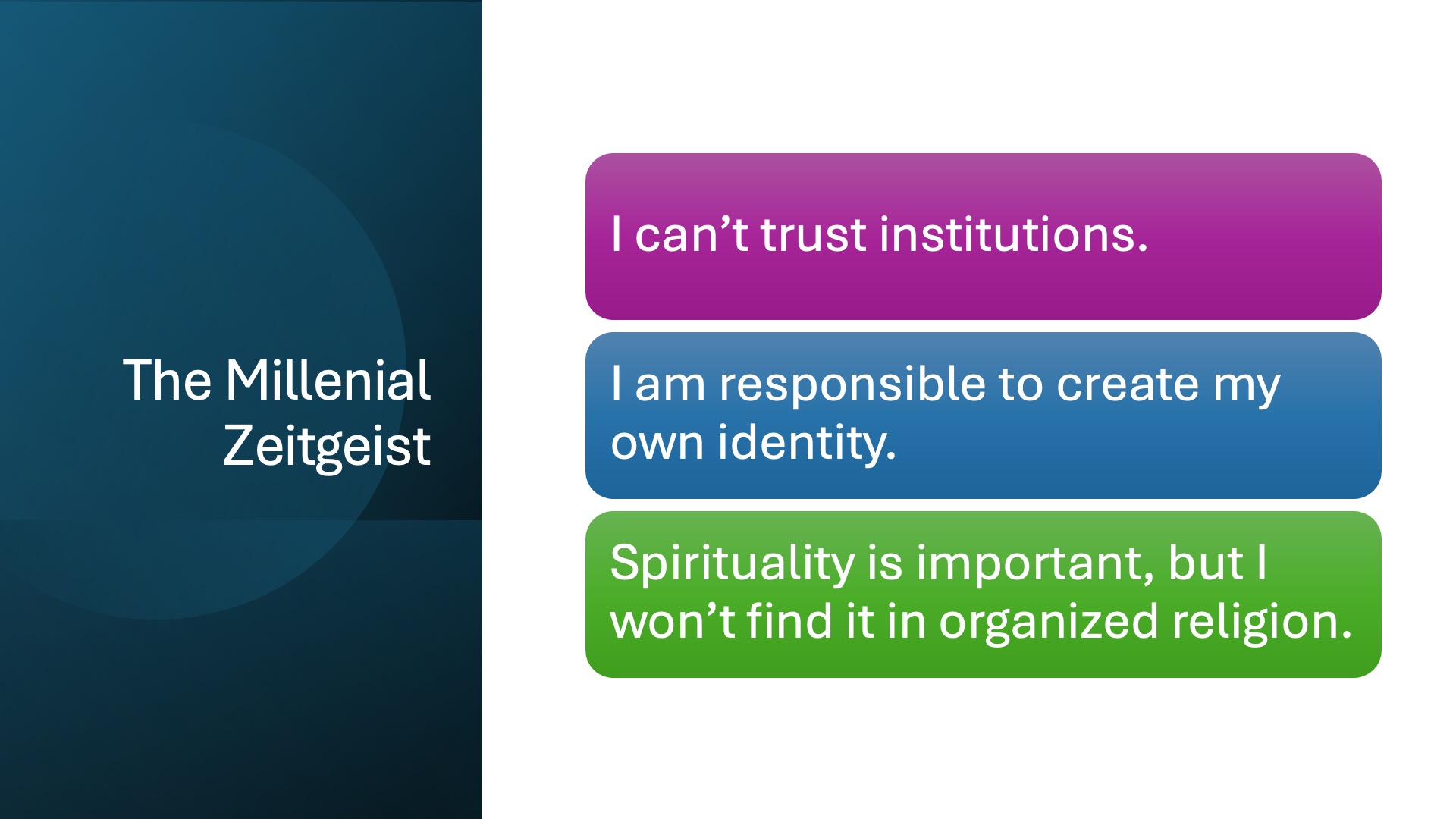

The first is Christian Smith, whose book Why Religion Went Obsolete (Oxford, 2025) explores what he calls the millennial zeitgeist—the spirit of our age and why institutional religion no longer holds the same relevance it once did.

The second is Ted A. Smith, in The End of Theological Education (Eerdmans, 2023). Although his focus is on seminaries, his analysis of social change in the twentieth century helps us understand what has happened to the church more broadly.

And finally, Diana Butler Bass, whose lecture Theology in a Time of Rupture paints a sweeping picture of the twentieth century as a series of seismic cultural shifts. I had the privilege of illustrating one of her presentations, and her insights have deeply influenced my thinking.

These three voices—alongside thirty years of pastoral ministry and my own work in missional leadership—form the framework for what follows.

When Church Was the Center

For much of the twentieth century, it was simply normal to go to church. To be a “good American” and a “good Christian” were nearly the same thing. Churches stood in the center of town, and the rhythms of community life revolved around Sunday worship.

For much of the twentieth century, it was simply normal to go to church. To be a “good American” and a “good Christian” were nearly the same thing. Churches stood in the center of town, and the rhythms of community life revolved around Sunday worship.

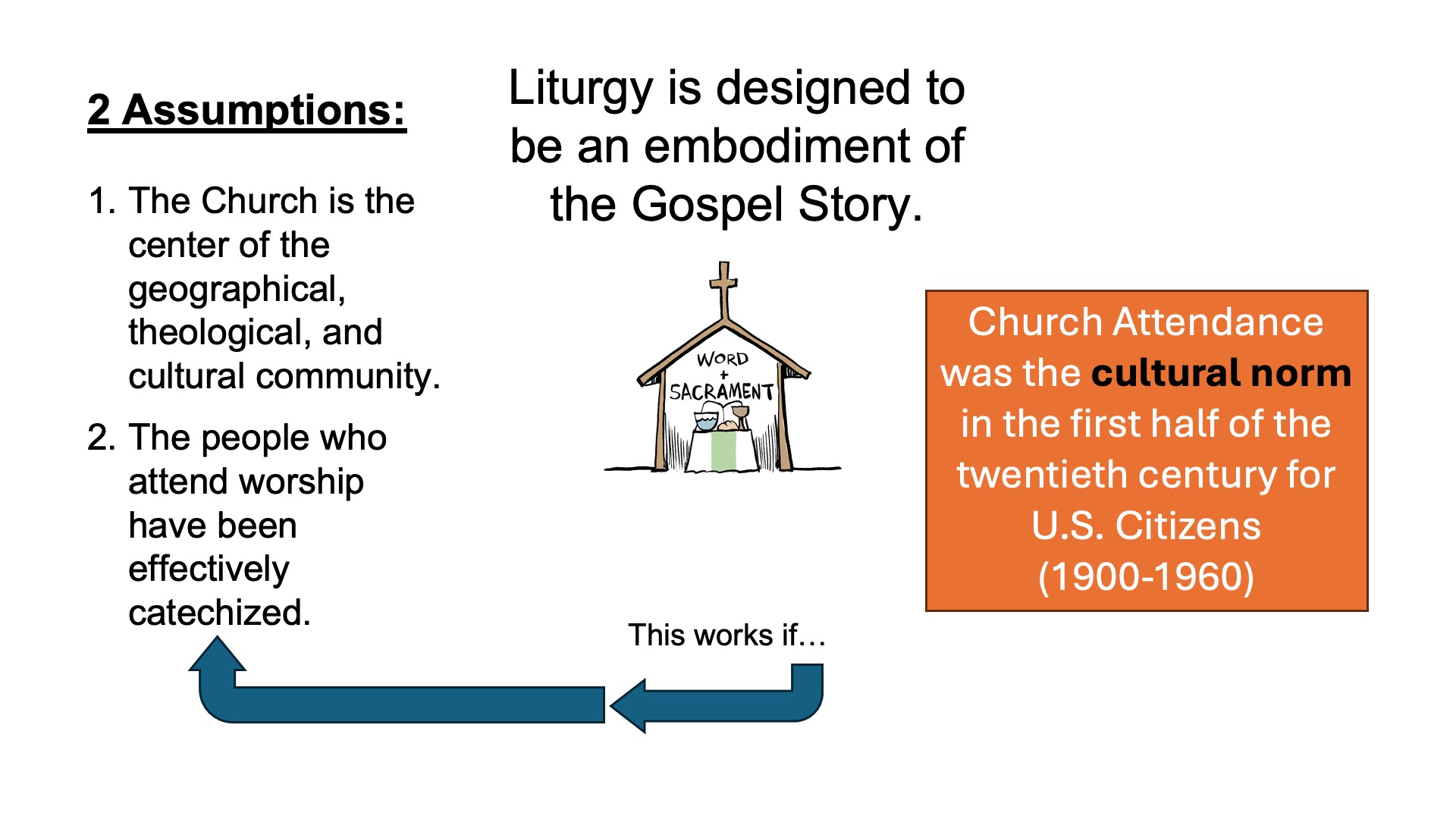

The liturgy—the structure of the service—was not just ritual; it embodied the story of the gospel. This way of being church was both good and beautiful, and it worked well as long as two things were true:

- The church was the center of the geographical, theological, and cultural community.

- The people who attended were effectively catechized—they understood the meaning behind what they were doing.

But in 2025, those assumptions no longer hold. The church is not the center of our culture. And many who attend, or once attended, have not been formed by the story of the gospel in the same way previous generations were.

That raises a larger question: What is at the center of our society now?

The Long Story of Change

To understand how we got here, we have to step back and look at the larger story—the movement from medieval Christendom to the modern world.

In medieval Europe, to be European was to be Christian. The church was literally the center of everything—geographically, politically, and socially. Kings ruled “by divine right,” and faith was bound up with power.

But that world began to unravel in the eighteenth century with the Enlightenment. Philosophers and scientists challenged the church’s claim to truth, insisting that knowledge should rest on reason rather than revelation.

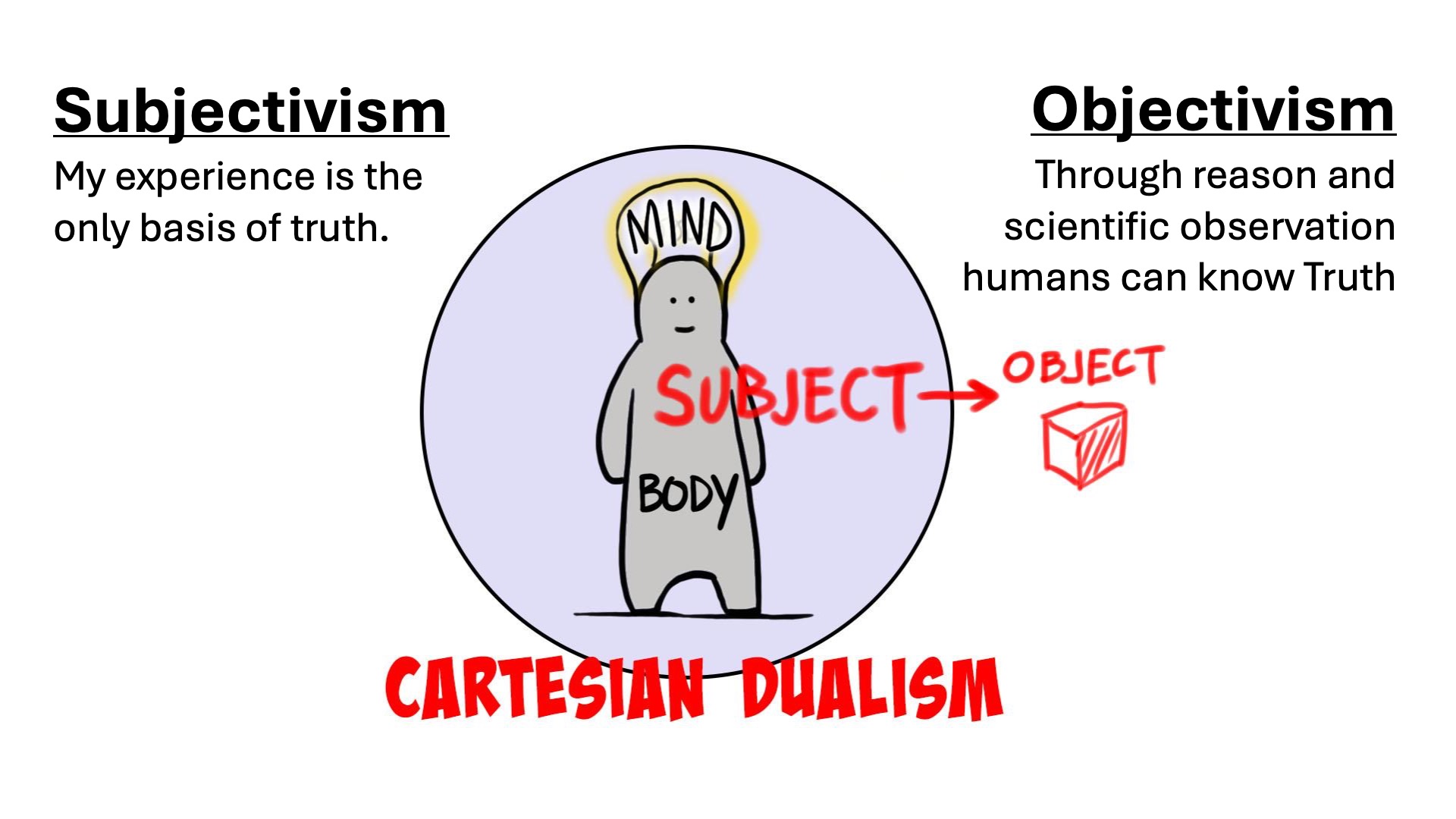

Two competing ways of understanding truth emerged.

-

Objectivism taught that truth could be discovered through rational observation—the foundation of the scientific method.

-

Subjectivism argued that ultimate truth was unknowable, and all we could trust was our own experience.

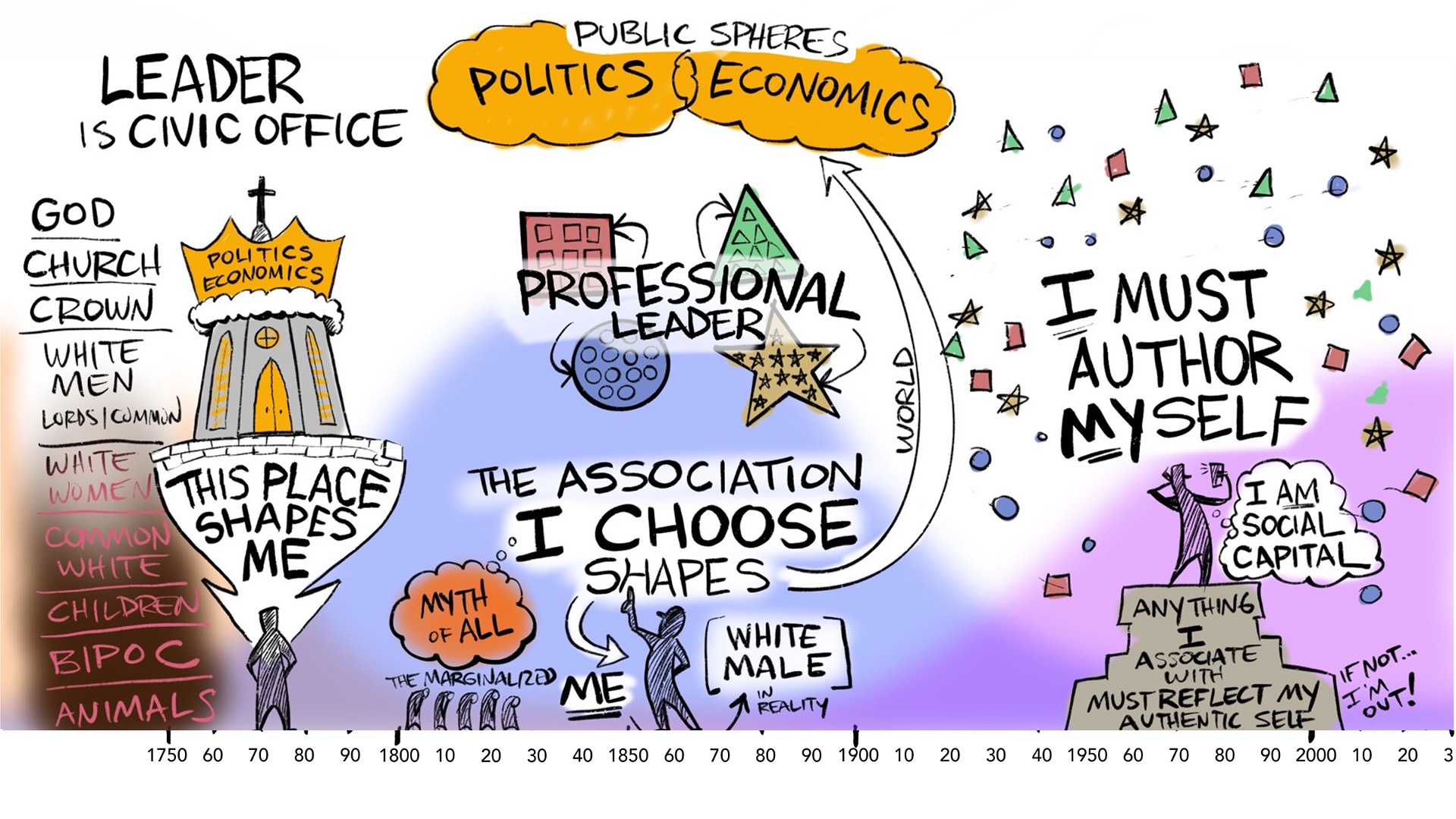

Together, these forces gave birth to the modern age, which replaced inherited identity with chosen identity.

The American Experiment

In America, that shift took on a new form. The American Revolution didn’t just create a nation; it created an imagination. No longer were we defined by where we were born or our social class. We were told that we could choose our own destiny.

This idea—radical individualism—became the heartbeat of American culture. It fueled expansion, industry, and the myth of self-made success. It also changed how people experienced religion.

In medieval villages, there was one parish church. In America, there were many. The church became a voluntary association—something you joined because you wanted to, not because you were born into it.

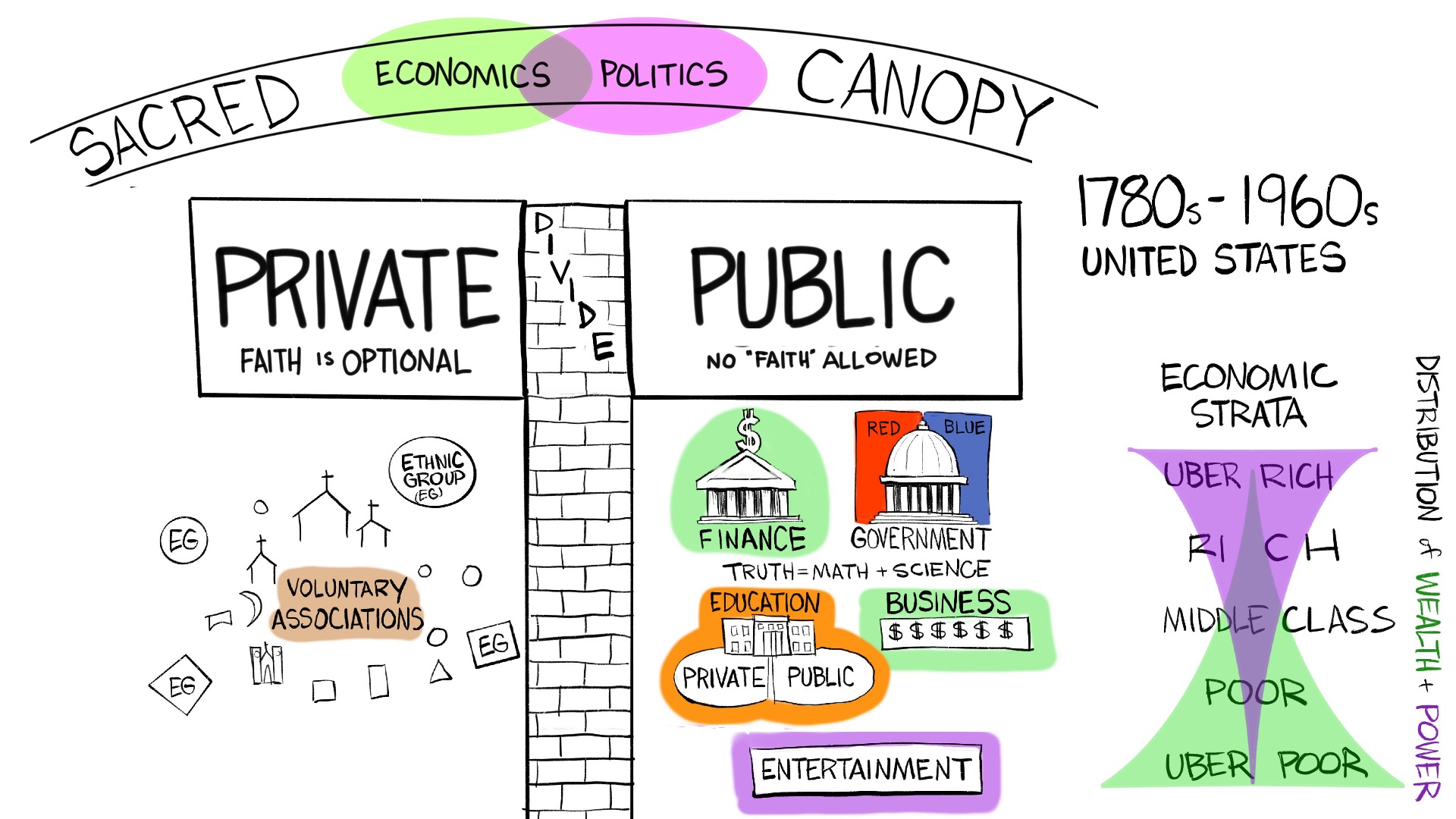

Faith moved from the public sphere to the private one. Public life was governed by science and politics; religion became personal, even optional.

The Church in the Twentieth Century

By the mid-twentieth century, the United States was thriving economically and culturally. Church membership was high, especially in the postwar years. But as sociologist Christian Smith points out, religion had subtly changed.

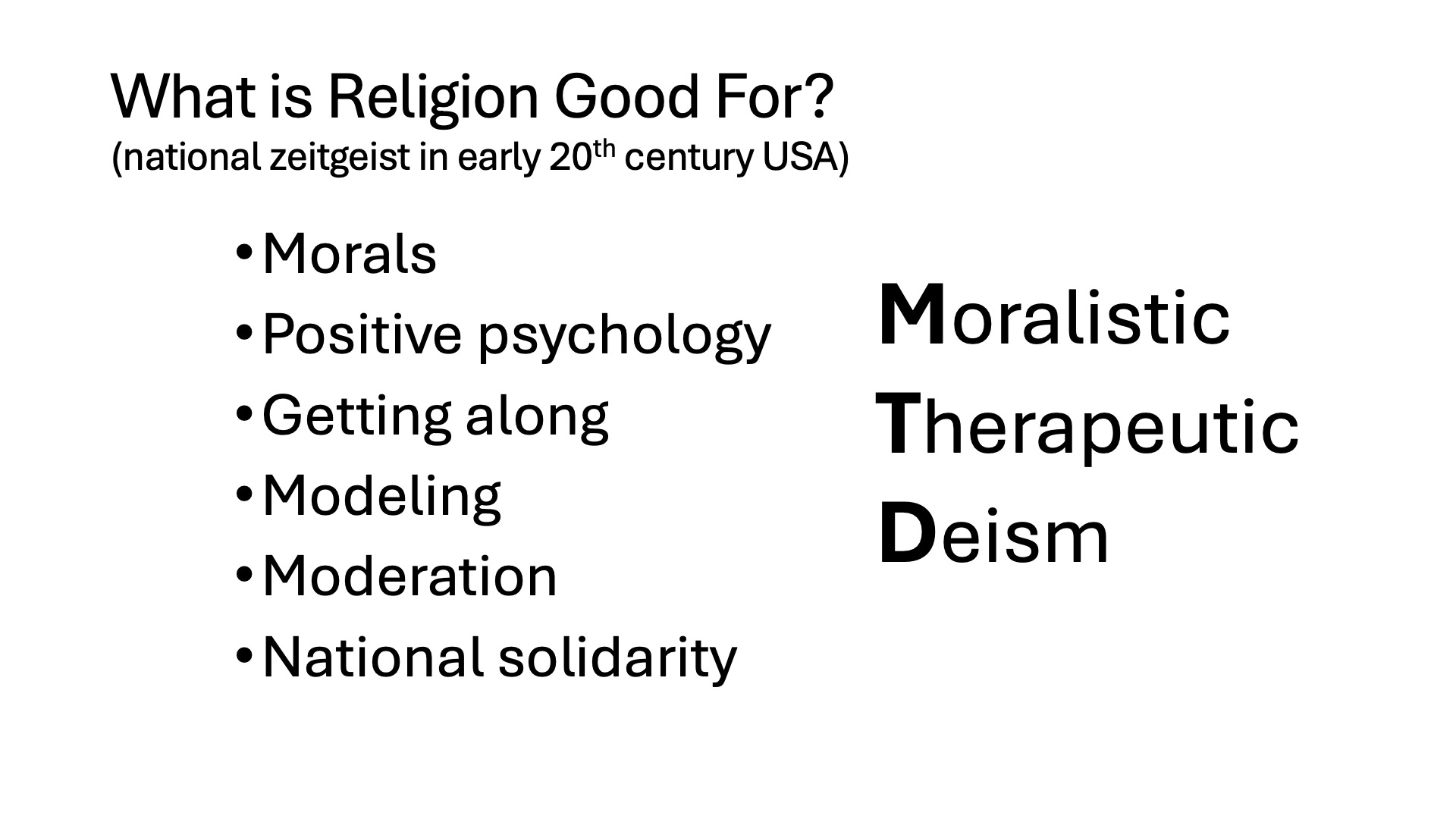

For many Americans, faith became primarily about morality, happiness, and belonging. It taught people how to be good, helped them feel better, and offered community support. Smith calls this Moralistic Therapeutic Deism—moralistic because it teaches right and wrong, therapeutic because it comforts us, and deistic because God is distant, uninvolved in daily life.

This version of religion worked well enough in the 1950s and early ’60s, when society was relatively stable. But it could not withstand the ruptures that were about to come.

Theology in an Age of Rupture

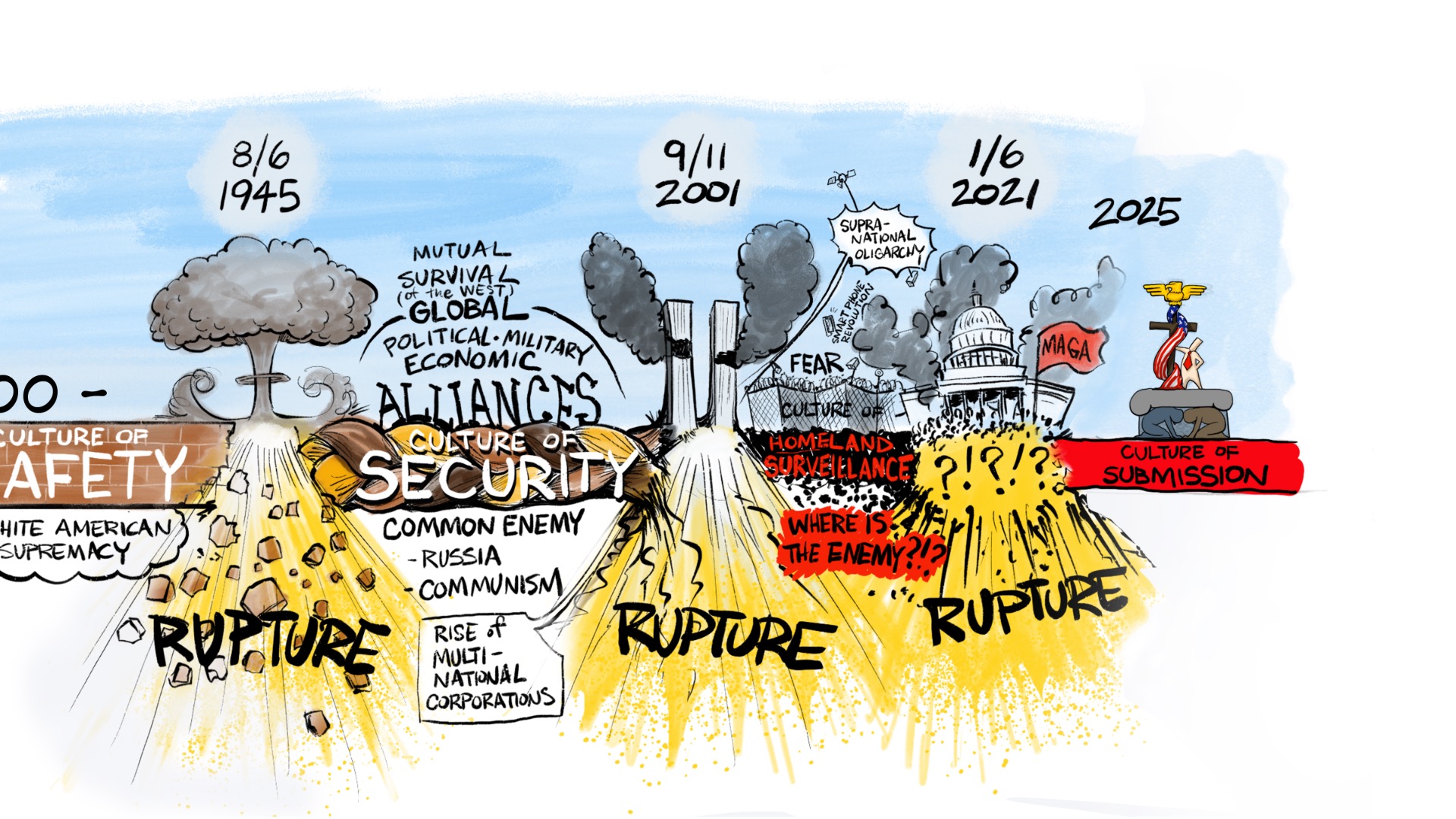

Diana Butler Bass describes the twentieth century as a time marked by three great ruptures—moments when the world as people knew it fell apart.

The first rupture came with the nuclear age. The optimism of the Industrial Revolution and the promise of science and the age of safety ended in mushroom clouds over Japan. The illusion that progress would save us was shattered.

This rupture hurled us into the second half of the century and an age of security. National security was dependent upon global alliances with demoncratic nations in NATO. The Cold War pitted capitalism against communism, and the triumph of “free markets” reshaped every aspect of life. Globalization, neoliberal capitalism, and the emerging digital landscape launched the US Economy into a new age of possibilities. By the 1990s, multinational corporations and digital technology promised endless prosperity. But beneath that optimism lay growing inequality and a deep spiritual emptiness.

The second rupture came on September 11, 2001. For the first time since Pearl Harbor, Americans felt vulnerable on their own soil. The myth of security was gone. The world entered a new era—an age of fear, surveillance, and constant connectivity.

Then, of course, came the pandemic of 2020 and the political chaos that followed. This led to the third ruptue: the storming of the capital on January 6, 2021. Many people now live with chronic anxiety. Institutions that once commanded trust—government, media, and yes, the church—are seen as corrupt or irrelevant.

Bass suggests that we have entered what she calls a culture of submission: a time when people are pressured by an authoritarian government to conform, but don’t really believe in the systems they’re serving.

From Association to Self-Authorship

Ted Smith argues that we have moved from an age of association to an age of authenticity and self-authorship.

In earlier generations, we found our identity through the groups we belonged to—family, church, nation. Today, identity is something each individual must create for themselves. We no longer ask, “Who am I?” We ask, “Who do I want to be?”

That shift has enormous implications for faith. Millennials and Gen Z are not less spiritual—they are simply living in a different story. They are seeking meaning and belonging, but they don’t trust institutions to provide it.

The Weight of Individualization

Ted Smith helps us understand this deeper. He distinguishes between individualism—the belief that individuals are autonomous—and individualization—a social process that forces us to constantly define and perform ourselves.

In our digital economy, each person becomes a brand; a form of social capital. Our worth is measured by visibility, productivity, and engagement. Even religion can become a form of self-expression—a curated identity rather than a shared faith.

This can be exhausting. Beneath all the noise of self-promotion lies a longing to be known, loved, and grounded in something bigger than ourselves.

What Is at the Center?

So, what’s at the center now?

For much of history, the church stood at the center of community life. That world is gone. But maybe that’s okay. Maybe this moment invites us to remember what the church was always meant to be—not a cultural institution, but a community of disciples following Jesus together.

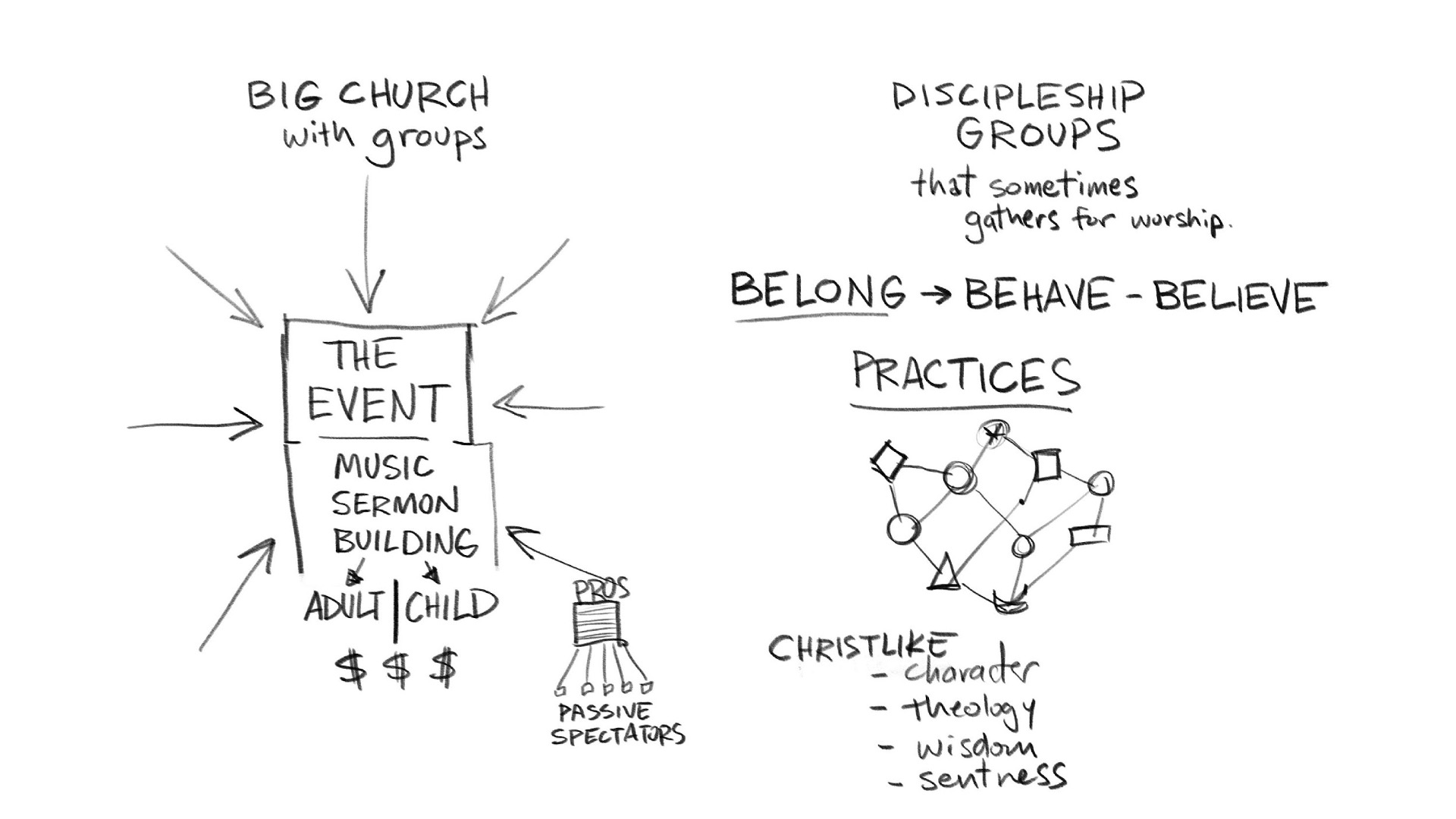

Discipleship means apprenticing ourselves to Jesus. It’s not about buildings or programs. It’s about learning to love God with all our heart, mind, soul, and strength, and to love our neighbors as ourselves.

Perhaps our calling today is not to get people back into the pews, but to embody the love of Christ wherever we are—to create spaces of belonging, reflection, and shared practice where people can encounter the living God.

A Word to Parents and Grandparents

If you’re a parent or grandparent wondering why your children don’t go to church, I want to say this gently: it might not be because they’ve lost faith. It may be because the forms of church that made sense to us no longer connect with the world they inhabit.

Instead of focusing on bringing them back into the building, maybe our calling is to help them see Jesus in us—to be living witnesses of grace, curiosity, and love.

The younger generations are still searching for truth and belonging. They’re still hungry for purpose. What if the Spirit is already at work among them, outside the walls we built?

This was an excellent video! So educational and thought provoking! Thank you!

That has given me some insight to creating communities

As a grandmother I found this article on “Why Don’t My Grandchildren Go To Church” of great interest. This (comment) comes up often in our groups. It has helped me understand a bit more of how to approach the subject with the group and with kids. I’ll pass this link on to others. Hopefully this will help them as well. Thank you for such an in-depth analysis of this issue.

You’re welcome. I’m glad you found it helpful.